The Charm of the Chams

Dramatic spiritual complexes built by the ancient Cham people with their intricate details dot parts of the Vietnam landscape. Their origins and the significance of their lasting contributions are explained by Ron Emmons.

Words & Photos Ron Emmons

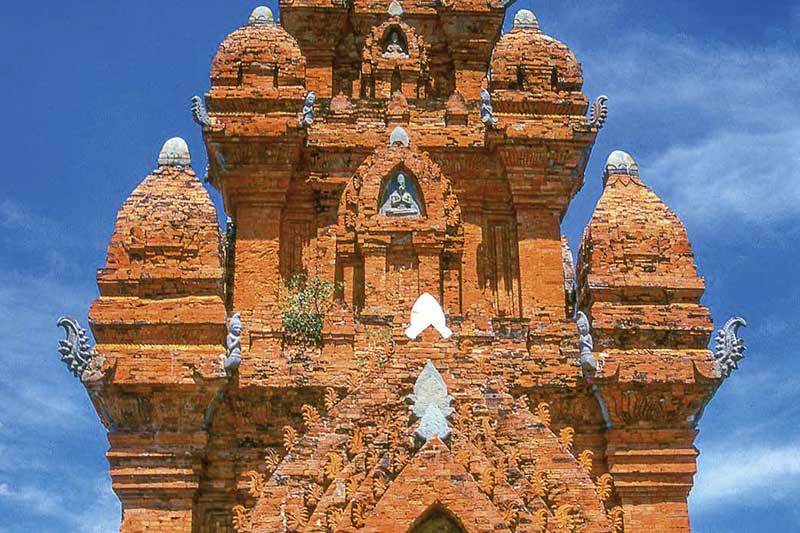

If you travel along Vietnam’s central coastline, you’re likely to spot some striking brick towers standing on hilltops; these are ancient Cham temples. Visitors heading for the beach resorts of Mui Ne or Nha Trang built over a thousand years ago.

On the road leading into Mui Ne from Phan Thiet, the Po Sah Inu Towers gaze out from an isolated spot above the South China Sea, while on a hill above Nha Trang, huge brick columns line the entrance to the Po Nagar Temple. This is dedicated to a local goddess, Yan Po Nagar, who is venerated in the main tower. A carving of Durga, a female warrior goddess with whom Yan Po Nagar is identified, adorns the pediment above the entrance to the temple. So who are these Chams, the creators of such beautiful structures?

As just one of Vietnam’s 54 ethnic groups, these days the Chams are largely a forgotten people, with a population of around 160,000. Yet for centuries they have clung on to their traditional ways, which differ from mainstream Vietnamese culture in almost every aspect. They have their own language and script, which is derived from Sanskrit. Matriarchal in society, women initiate marriage proposals, pass their family property to daughters, not sons. Young girl receive careful protection, and great importance is placed on virginity. A Cham saying goes “As well leave a man alone with a girl as an elephant in a field of sugar cane.”

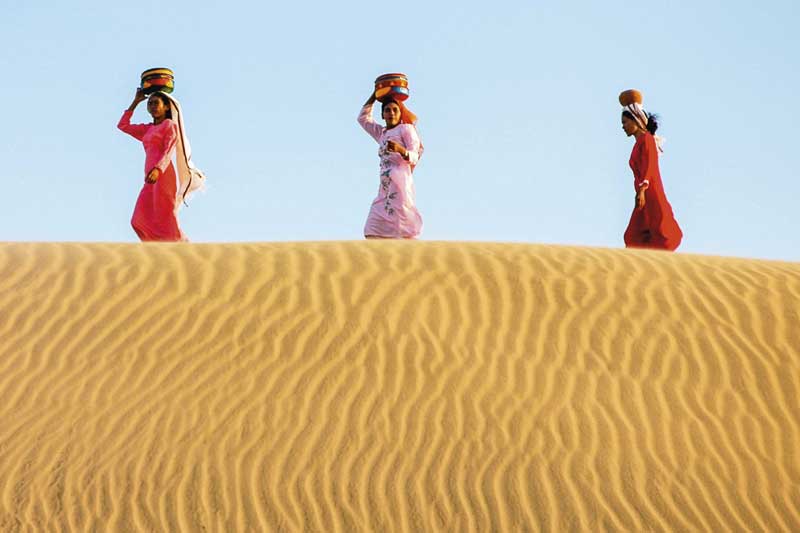

The women and highly skilled in pottery and weaving, particularly brocade, and the men play unique musical instruments, such as the xaranai, a type of clarinet, and the paranung, a cylindrical drum. These are put to good use in Cham festivals, particularly the Kate festivals, particularly the Kate festival, which honours past kings and ancestors, and takes place in late September or early October each year. For three days, the Chams celebrate by making and eating ginger cakes, dancing and singing, and carrying offerings to their local temple, which is housed in an ancient brick tower.

A thousand years ago, the Chams were one of the most feared peoples in Asia, frequently fighting pitched battles with their sworn enemies, the Khmers and the Dai Viet. Their Champa Kingdom, established in the second century, occupied what is now Central Vietnam, as well as parts of modern-day Laos and Cambodia, and the Chams were also undisputed masters of the South China Sea (then known as the Champa Sea). Then in the 15th century they were heavily defeated by the Vietnamese, and many of them fled west to neighbouring Cambodia, though a large number stayed in Vietnam.

They practised Hinduism, probably because of trade with Indian merchants, and they used the wealth accumulated from selling goods such as spices and sandalwood to finance the building of eye-catching towers in which to worship their Hindu gods. Later, many Chams converted to Islam, so they split into two groups – the Balamon Cham, following Hinduism, and the Bani Cham, following Islam.

Most of the Balamon Chams live in villages around the towns of Phan Thiet and Phan Rang on Vietnam’s south-central coast, while the smaller group of Bani Cham are predominantly based in the Mekong Delta around Chau Doc. Both groups make their living from fishing, farming, and making handicrafts.

Traditionally, both men and women wear a kind of sarong, as well as a scarf or turban. Travellers who venture into their territory find most Chams living in thatched huts made of mud, straw and bamboo, with no running water or electricity. Yet despite the appearance of poverty, they are a welcoming, fun-loving people. It strangers wander into their village, the locals will usually invite them to a cup of tea and maybe a snack of rice crackers.

Several generations live together in their simple houses and the children help with tasks like gathering firewood and caring for their animals, such as goats and water buffalo. When they have free time, the kids are out playing on nearby sand dunes or inventing games, such as throwing their sandals to see who can get nearest to a chosen target. As for cuisine, they are particularly keen on sour soups made with local ingredients, such as young tamarind leaves and frogs in the rainy season.

In recent years, Vietnamese authorities have come to appreciate the appeal of the country’s diverse ethnic groups to visitors, and funds have been provided to promote their culture. As a result, many of the Cham towers that are scattered around the landscape between Da Nang and Phan Thiet have now been carefully restored, revealing a sophisticated sense of design. The bricks are crafted so skillfully that no mortar is necessary to hold the buildings together, and the bricks are also often carved into images of elephants or mythical creatures that decorate the exterior of the towers.

One of the best-preserved Cham temple complexes is the Po Klong Garai Temple, located on a hill near Phan Rang, built in the late 13th century. The temple features a gorgeous carving of Shiva ove the mandapa and considered a masterpiece of Cham sculpture. Many Cham towers see dedication to Shiva, though some honour local kings or other Hindu deities.

A Cham temple complex consists of four principal elements. The main sanctuary, or kalan, houses the particular deity (often Shiva) that is worshipped here.

The entrance hallway that leads to the central sanctuary is called the mandapa, while a separate building with a saddle-shaped roof, the kosagrha, is used for storing objects relating to the deity. Finally, the gopura is an arched gateway that leads into the temple complex.

For anyone intrigued by Cham culture, a visit to the UNESCO World Heritage Site of My Son (pronounced ‘mee sern’) is a must. American bombs destroyed much of this temple city during the 1960s, but restroration work has been going on steadily and the site, surrounded as it is by lush green hills, exudes an eerie spirituality. Though comparisons with Angkor are inappropriate as the scale here is much smaller, the silent evidence of a highly developed ancient culture is similarly awe-inspiring.

An informative museum at the entrance to the complex helps visitors to identify different aspects of temple architecture, as well as strange mythical creatures such as the gajasimha, a combination of lion and elephant, and the hamsa, a mythical bird. Despite its remote feel, My Son is just a short ride from either Hoi An or Da Nang, so it’s easy to get to, but since a visit entails a lot of walking, it’s better to go there either or late in the day to avoid the midday sun.

Besides being innovative and accomplished temple builders, the Chams are also excellent sculptors in stone, and this is clear to see at the Da Nang Museum of Cham Culture, which makes an ideal first or last stop on a tour to learn about the Chams. Most of the exhibits are huge slabs of sandstone that were meticulously crafted centuries ago, and were later removed from the Cham temples they adorned for safekeeping. Delightful depictions of Hindu gods and mythical creatures reflect a vibrant culture that achieved great artistic heights in its heyday. Even today, though more subdued, Cham culture is alive and well, and thoroughly charming.