Teak Trails

How a timber boom helped shape the Kingdom of Siam

Words & Photos: Ron Emmons

Beginning of the Teak Boom

In the mid-19th century, the Kingdom of Siam was virtually unknown to the outside world, but that started to change in 1855 when King Mongkut of Siam and Sir John Bowring, representing the British government, signed what became known as the Bowring Treaty. This treaty guaranteed Siam its sovereignty in return for drastically reduced taxes on Siamese products such as teak and ivory, which led to an increase in international trade.

At the time, the region around Chiang Mai, formerly known as Lanna, was still an independent kingdom, though its ruler or chao paid triannual tribute to the King of Siam. This in itself was an arduous undertaking, involving at least a month on a boat going downstream to Bangkok bearing gifts and then an even longer journey back upstream to the north.

In those days, the hills around Chiang Mai bristled with teak, which was in great demand for building ships by colonial powers such as Britain and France, both eager to expand their empires. In 1882, a shipment of teak from Bangkok to Liverpool was auctioned for twice the expected price, and the teak boom took off.

Establishments like the Borneo Company and Bombay Burmah Trading Company opened offices in Bangkok and hired agents to control their operations in the northern hills. The agents negotiated concessions with the local ruler to log the forests and sent gangs of loggers and elephants into the jungle to fell the trees.

Elephants and Teak Logging

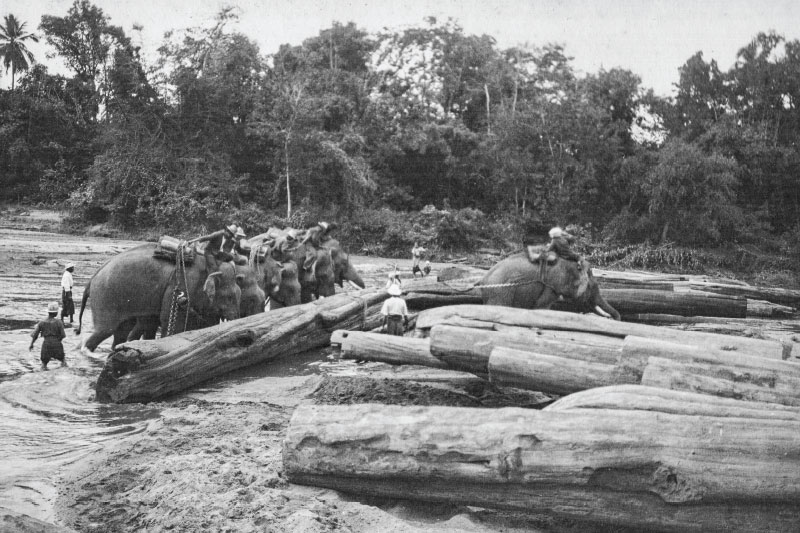

Without elephants, teak logging would have been unthinkable. In those days before machines, only elephants were capable of hauling logs weighing several tonnes from where the tree was felled to the riverbank, ready to be sent downstream in a teak raft.

There were many steps in teak logging, and the whole process, from girdling trees to selling planks of teakwood at the sawmills in Bangkok could take five years or more. Girdling involved removing a strip of bark and sapwood from the circumference of the tree, which kills it within a few years. Felling was a particularly precarious process; if the tree fell the wrong way, it could split the trunk or crush the loggers, so wedges were shoved into axe cuts to make the tree lean the right way.

The least favoured job for teak loggers, however, was ounging, which involved taking a group of elephants to the heart of a logjam on a river, getting them to prise out the jammed logs and hope they would not all be swept away in the ensuring rush of water.

Years of drought could also be disastrous, since the rivers would not rise enough to float the logs downstream, and the teak agents were left cursing their bad luck.

Nevertheless, when conditions were good, teak trading cold be a very lucrative business, and the teak tycoons built themselves lavish homes run by retinues of servants.

Siam Spreads North

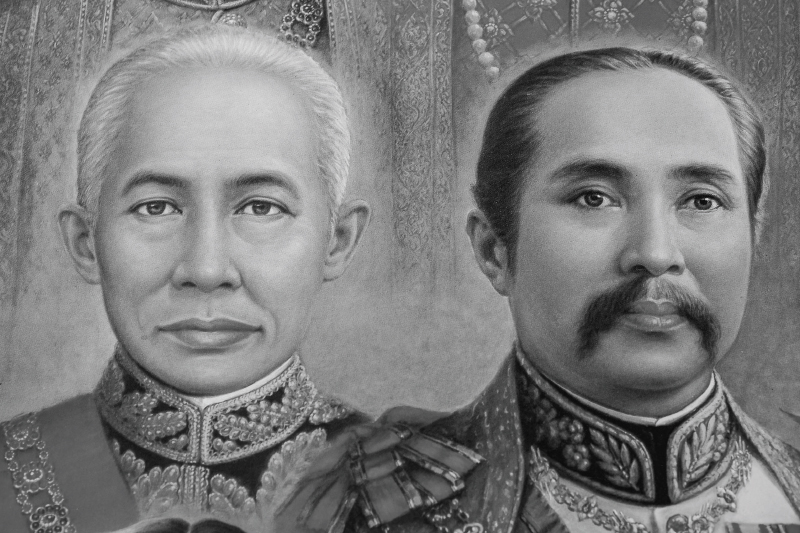

In the 1880s, the profitable teak trade in Chiang Mai began to attract the interest of Britain and France as well as Siam. When Britain annexed Upper Burma and France pushed west from Vietnam to Laos, it seemed that either nation might snatch this remote land, but the stealth of the Siamese beat them to it with a series of laws that gradually eroded the powers of the local ruler. The deal was virtually sealed by an act of regal diplomacy. When King Chulalongkorn of Siam heard that Queen Victoria of Britain wanted to adopt Dara Rasamee, daughter of Chiang Mai’s ruler Chao Inthawichayanon, he stepped in and took the 13-year-old princess as a consort to Bangkok. By the end of the 19th century, Chiang Mai and the northern provinces were incorporated into the Kingdom of Siam.

Just over a century later, Chiang Mai is one of the most popular destinations for domestic tourists, partly because its language, culture and cuisine set it apart from mainstream Thai culture. So let’s follow the teak trail to landmarks that carry echoes of the teak boom era.

Following the Teak Trail

A good place to start is right in the heart of Chiang Mai’s old walled city at a building formerly known as the Khum Chao Burirat, which was built for a high-ranking official in 1889. These days it is home to the Lanna Architecture Centre and is a classic example of a style known as Lanna Colonial, which combines features of Western and Eastern design. The ground floor of bricks and mortar with its shady colonnade is typical of Western colonial style while the upper floor of teak with its breezy veranda is ideal for the humid Thai climate.

From here, hop to the Ping River Footbridge, which was actually the first permanent bridge over the Ping River when it opened in 1890. It was initially built of teak by Marion Cheek, a wealthy teak trader (see sidebar) and it stood for many years before it was broken by the steady stream of teak logs from the north. These days its concrete replacement is known as the Jansom Memorial Bridge, which joins Wat Ketdaram on the east bank and Warorot Market on the west.

Just a block east of the bridge is the 137 Pillars Resort, which boasts as its centrepiece the former office of the Borneo Company in Chiang Mai in the days when Louis Leonowens (see sidebar) was their Chiang Mai agent. Non-guests are welcome to come in for a peek or to enjoy afternoon tea in the super-sophisticated setting.

Also on the east bank of the Ping River, about a kilometre downstream, lies the Chiengmai Gymkhana Club, where the teak agents used to meet for cocktails and matches of cricket, golf and polo. The club is still popular haunt, and its terrace which looks out over a lush green golf course from the shade of an enormous rain tree is the perfect place to enjoy a sundowner at the end of our teak trails tour.