Unearthing Lanna’s Lost City

Discover Wiang Kum Kam, the ancient capital buried in Chiang Mai’s suburbs

Words: Ron Emmons

Photos: Ron Emmons & Shutterstock

It’s common knowledge that Chiang Mai, now the main city of North Thailand, was once the capital of a kingdom called Lanna, meaning “a million rice fields”. But few are aware that before 1296, when Chiang Mai was established, that honour fell to a city called Wiang Kum Kam.

So where is this Wiang Kum Kam? And why is it so unknown if it was at the heart of a growing empire? The first question is easy to answer, but the second needs more explanation.

Wiang Kum Kam is hidden in plain sight, just six kilometres south of downtown Chiang Mai, squeezed between two ring roads and long ago encompassed by the city’s relentless expansion.

Now that we know where it is, let’s consider how it was lost, why it was forgotten and what remnants are worth visiting today.

When King Mangrai (sometimes spelled Mengrai; see box) took possession of Haripunjaya (now Lamphun) in 1283, he decided to base his new kingdom at Wiang Kum Kam on the west bank of the Ping River, and had a moat dug to protect his new capital.

Unfortunately, the area was prone to flooding, and within a few years Mangrai decided to move his capital further upstream after seeing several auspicious signs, including fearless deer at the foot of the mountain Doi Suthep. He founded Chiang Mai on the plain between the mountain and the Ping River, and the rest, as they say, is history.

While Wiang Kum Kam continued to be inhabited, the problem of flooding did not abate, and in the early 16th century, so archaeologists believe, the city was hit by a disastrous flood that buried most buildings with sediment, and those who survived abandoned the site.

This extreme weather event may also have been the cause of the Ping River changing its course, which happened around the same time, leaving Wiang Kum Kam on its east bank where it had once been on the west bank; an unusual case of a city being relocated without actually moving.

Submerged under sediment, with nothing visible but the tops of stupas, the city was gradually forgotten and Wiang Kum Kam disappeared form history.

The site continued to be ignored during much of the 20th century and was gradually occupied by residential houses, until in the 1980s the Thai government’s Fine Arts Department announced that it was going to unearth Lanna’s lost city.

Now, some 40 years on, the remains of over 40 temples have been revealed, though most of them consist of little more than brick foundations, a stupa and a boundary wall, so an exploration of the entire site would be a bit repetitive.

Fortunately, there are pony and carriage teams (or electric carts for big groups) waiting to take you round nine of the most interesting temples. The ride takes around 45 minutes and costs 300 baht per carriage (400 baht per electric cart).

The tour begins at the Wiang Kum Kam Information Centre (https://www.facebook.com/WiangkumkamInformationCenter), just east of the Ping River on the middle ring road, where relics from the site such as stucco carvings provide a tantalising introduction. The pony riders speak little English, so during the tour, look out for information boards giving what little history is known, as well as QR codes at some sites that link to short, informative videos by the Fine Arts Department.

Unlike Thailand’s World Heritage sites at Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, which have been cleared of all modern sights, Wiang Kum Kam’s temples sit shoulder-to-shoulder with modern houses, stores and workshops, so a visit gives a glimpse of contemporary suburban life as well as opening a window on the past.

The first temple passed on the tour is Wat Ku Pa Dom, where the brick foundations of an assembly hall, ordination hall, stupa, well and boundary wall sit a couple of metres below the surroundings land. An angled retaining wall here and at other temples along the way is designed to prevent further damage from flooding.

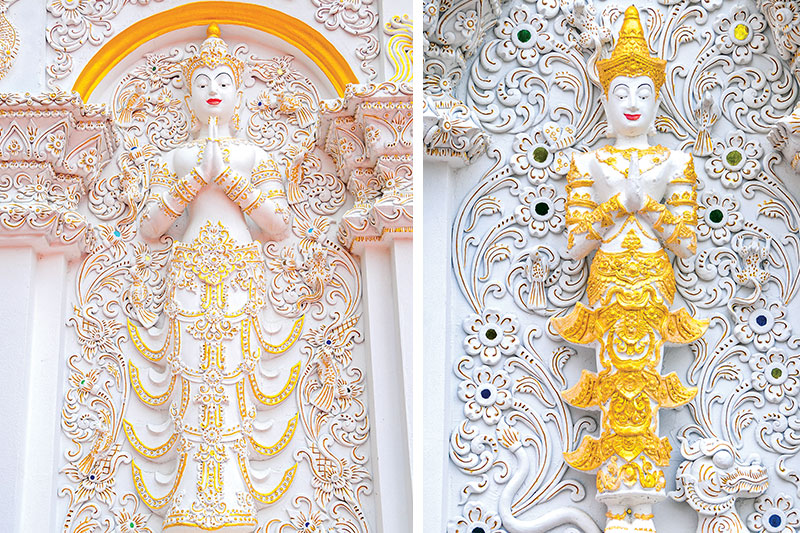

One of the most important sites is Wat Chang Kham, a modern temple built on the site of an older temple, Wat Kamthom, which is where excavations of the ancient city began in 1984. All that remains of Wat Kamthom is the base of the viharn and stupa, but several elements of Wat Chang Kham are of interest, including a shrine to King Mangrai, a wonderfully decorated scripture library, several statues of mythical creatures and a bodhi tree supported by colourful poles.

The ruins of Wat E-Kang and Wat Pupia are probably the best preserved of the ancient sites. Both feature a stupa and the remains of several buildings, though as elsewhere the retaining walls show how the brick foundations are well below ground level. Wat Pupia is the only temple with some elements of stucco carvings remaining near the top of the stupa.

The temples’ names hint at the difficulty of guessing their origins, as no records are available from that era. For that reason, they have been named after modern associations. Wat E-Kang’s name is derived from a group of monkeys that once inhabited the area and Wat Ku Pa Dom was named after the landowner before excavation.

The pony makes a final stop in the shelter of trees at Wat Chedi Liam, which appears to be a modern temple, though the square stupa with five receding levels and Buddha images in niches was first erected by King Mangrai in memory of his wife. Take the chance to wander round the tranquil site with its brightly decorated assembly hall, ordination hall and spirit houses, then hop back in your carriage for the last leg of the ride back to base.

Mighty Mangrai

King Mangrai (1239-1317) inherited his father’s kingdom at Chiang Saen in 1259 and then in 1262 he established Chiang Rai, which he named after himself. From there, he extended his power westwards to Fang and then southwards, ousting the weak Haripunjaya Empire and founding his own Kingdom of Lanna at Wiang Kum Kam in 1285. Rather than fight the floods there, he relocated upriver to Chiang Mai, which became the new capital of Lanna in 1296. There he reigned supreme until one day, as legend has it, he was stuck down by a bolt of lightning in the exact centre of the old city.

Despite his prowess as a warrior, Mangrai is remembered for an act of diplomacy. When King Ngam Muang, ruler of Phayao, found out that King Ramkhamhaeng of Sukhothai had slept with his wife, Ngam Muang was all for executing his rival. But Mangrai persuaded him accept a payment from Ramkhamhaeng to atone for this misdemeanour.

After this, the three rulers became firm friends and Mangrai’s new allies helped him plan his “new city” (Chiang Mai). As cameras and smartphones were not available in Mangrai’s day, we have no photographic evidence of his appearance. Yet there is a remarkable similarity in all the statues dedicated to him around North Thailand, rendering him with a perfect physique, handsome face and proud demeanour.

At Wiang Kum Kam, you can see his likeness in the Information Centre, and if so inclined, you can commune with his spirit, which is believed to reside in the elaborate spirit house at Wat Chang Kam.